A Deep Dive into the Financial and Economic Impact of Credit Scoring on the Everyday Ghanaian

July 1, 20256 minutes read

Credit scoring is quietly becoming one of the most powerful tools in Ghana’s financial system. For individuals, it’s changing the way they access loans, build trust with lenders, and take part in the formal economy. For banks and institutions, it’s reshaping how credit risk is assessed and managed. This analysis explores the ripple effects of individual credit scoring in Ghana, how it’s influencing financial inclusion, economic growth, and how our experience compares with global trends.

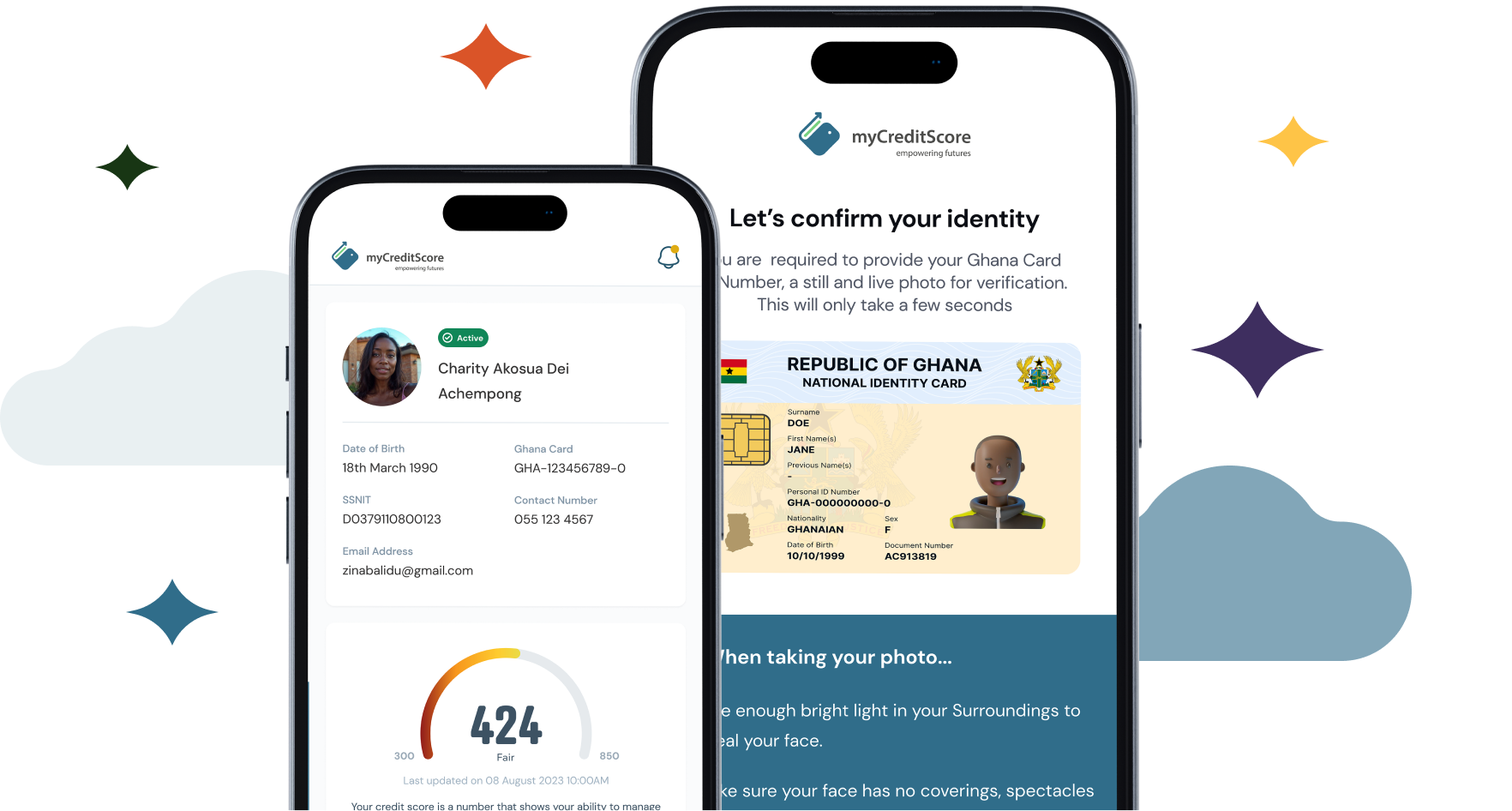

Ghana’s financial sector has seen rapid evolution over the last decade, largely driven by the widespread adoption of mobile money and digital banking tools. With more than 22 million mobile money users in the country, the shift from collateral-based lending to behaviour-based credit assessments is well underway. Tools like myCredit Score are making it possible for institutions to assess borrowers based on how they manage their money, not just what they own. This change is significant because it opens up access to credit for millions of Ghanaians who were previously excluded from formal financial systems.

The theory behind credit scoring is grounded in decades of economic research. Scholars like George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph Stiglitz, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics, developed the concept of information asymmetry, the idea that financial markets perform better when lenders have more reliable data about borrowers. In this sense, credit scoring is not just a tech innovation. It’s an economic solution to a human problem: how to build trust in lending relationships.

The World Bank has long identified credit scoring as one of the most effective ways to increase financial inclusion, especially in countries like Ghana, where many people operate outside traditional banking systems. In this context, mobile data, payment history, and digital transaction records are filling the gap where formal credit histories are missing.

Early results in Ghana are encouraging. The myCredit Score pilot program alone has already facilitated over 40,000 credit disbursements, totalling more than GHS 637,000. It has done this while maintaining a low default rate of just 2.51 percent and a non-performing loan rate of 3.44 percent. These figures point to better risk management and more efficient lending overall.

But the impact goes beyond banking. Research from the University of Ghana Business School shows that increased access to credit through scoring systems has led to more business formation, faster growth among small enterprises, and higher employment rates. It has also helped reduce dependence on informal lenders, especially in urban and peri-urban areas.

When you zoom out and compare Ghana to other markets, the benefits of credit scoring become even clearer. Kenya’s adoption of scoring through M-Shwari led to a 70 percent increase in microloan access and slashed processing costs by half. India’s credit scoring reforms transformed its MSME sector, increasing lending by over a third and reducing default rates by 45 percent. In Brazil, access to credit among low-income groups jumped by 40 percent after scoring models were implemented, while borrowers with good scores saw their interest rates drop by a quarter.

In Ghana, credit scoring has brought measurable improvements across three broad areas: financial sector efficiency, business growth, and consumer welfare. For banks and lenders, credit scoring has reduced operational costs, improved risk assessment, and allowed capital to be allocated more efficiently. For businesses, especially SMEs, the increased transparency has made it easier to qualify for loans, survive market shocks, and move from informal financing into the formal economy. And for consumers, scoring has made credit more accessible, especially for those with strong financial behaviour but little to no formal credit history. This has helped reduce borrowing costs and enabled better financial planning.

The ripple effects reach the broader economy as well. Studies from the African Development Bank suggest that a strong credit scoring system can contribute up to 2 percent to Ghana’s GDP growth annually, mostly through the expansion of the formal sector and improved lending velocity. The Bank of Ghana has also noted that financial institutions using credit scoring report significantly lower non-performing loan rates, which in turn enhances the resilience of the financial system as a whole. A more efficient lending sector also means that central bank policies can be transmitted more effectively.

Ghana’s legal and regulatory frameworks are keeping pace with this evolution. The Credit Reporting Act of 2007 provided the legal foundation for credit bureaus, while the Data Protection Act of 2012 ensures consumer privacy is respected. In recent years, the Bank of Ghana has also introduced more detailed regulations for alternative data use and digital lending platforms.

The country’s digital infrastructure has grown stronger in support of these changes. GhIPSS enables secure digital payments across banks and platforms. Mobile money providers continue to expand their reach and offer vital alternative data. And the Ghana Card is beginning to play a crucial role in identity verification, a necessary step in building trust in digital financial systems.

There’s much to learn from how credit scoring has been implemented in other countries. The United States, with its long-established FICO model, has seen consumer lending volumes grow significantly while reducing average lending costs. In Singapore, real-time credit decision systems, tied to national digital IDs, have created seamless and highly secure lending experiences.

Ghana’s path forward will depend on how well we scale current systems and address challenges. There’s still work to be done around data quality, especially when it comes to capturing informal sector transactions. Technical infrastructure needs to continue evolving to support real-time decision-making, cybersecurity, and system interoperability. And more must be done to close the gap in digital and financial literacy, especially in rural communities.

Still, the projections are promising. The World Bank and IMF forecast that credit scoring could drive 30 to 35 percent annual growth in Ghana’s formal lending market, while reducing lending costs by up to 30 percent. The SME sector alone could see accelerated growth of up to 20 percent. And financial inclusion could improve by as much as 45 percent in the coming years.

There are also opportunities to expand the models Ghana is using. Integrating new data sources like utility payments and public transport usage could make scoring systems even more inclusive. Artificial intelligence offers the potential to enhance predictive accuracy. And regional credit information sharing across ECOWAS countries could unlock new cross-border lending markets.

Credit scoring is more than just a technical improvement. It’s becoming one of the key drivers of Ghana’s financial transformation. By leveraging technology, regulation, and local insights, Ghana is building a more inclusive, efficient, and resilient financial system. If the momentum continues, Ghana could serve as a model for how credit scoring can unlock economic opportunity across Africa.